Microbes to the Rescue:

A One-Step Breakthrough for Plant Growth and Natural Pest Defense

In the era of sustainable innovation, a group of researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) has developed a microbial solution that has the potential to transform the future of agriculture—making crops both more resilient and intelligent in the fight against pests.

Jointly developed by researchers from the NUS Environmental Research Institute (NERI) and the Department of Biological Sciences (DBS), this technology has been recently patented under the title “Microbial Solution to Improve Growth Promotion and Pest Management in Plants” (Patent Application No. 10202403353Y), with inventors Dr. Teh Beng Soon, Mr. Mayalagu Sevugan, and Assoc. Prof. Sanjay Swarup.

Inventors of the “Microbial Solution to Improve Growth Promotion and Pest Management in Plants”

(from Left to Right): Mr. Mayalagu Sevugan, Assoc. Prof. Sanjay Swarup and Dr. Teh Beng Soon.

What makes this solution truly revolutionary? It’s a single microbial strain—code-named P33G—that promotes rapid plant growth and offers systemic pest protection, all without using any pesticides.

The fundamental breakthrough lies in harnessing the natural, symbiotic relationship between plants and microbes. “We have developed a single microbial solution that increases both plant growth and productivity, as well as plant tolerance to a broad range of insect pests,” shared Prof. Swarup. “These benefits are based on the ecological principle of multi-trophic interactions—plants, microbes, and insects.”

Once coated onto seeds, the P33G microbe moves through the roots and reaches into the leaves of the plant. There, it triggers a cascade of biological processes: accelerating photosynthesis, modifying hormonal pathways, and—perhaps most impressively—stimulating the plant’s own defense mechanisms.

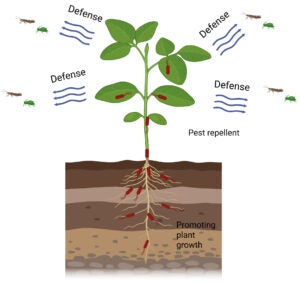

Schematic diagram shows plant growth promotion and insect pest repellent. Inoculation of P33G via seed dressing and around root zone for growth promotion. Migration of P33G from the root to leaves induces plant defense against insect pests.

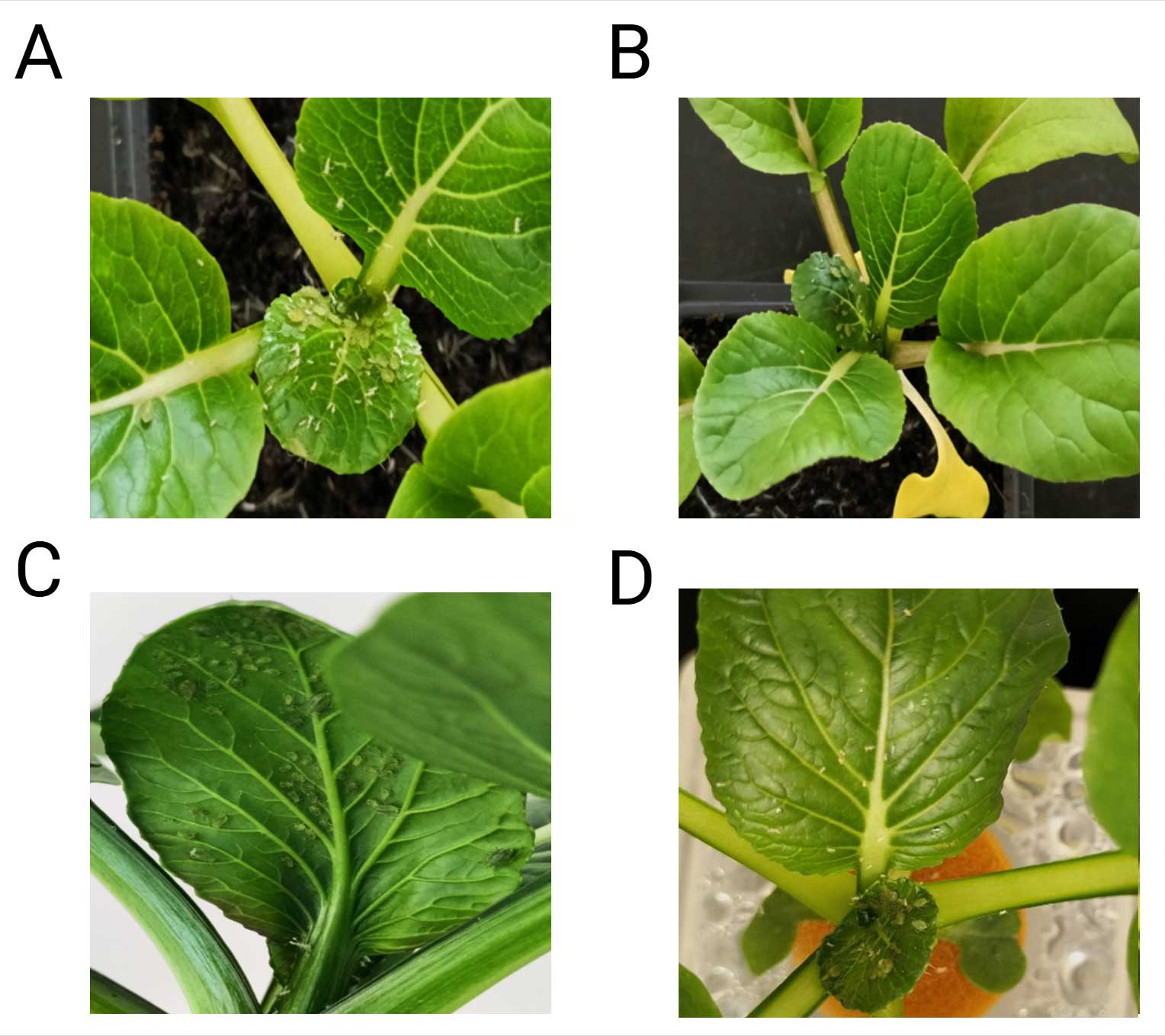

Aphid distribution between untreated and P33G-treated plants grown in soil and hydroponics.

(A) Untreated plants grown in soil; (B) P33G-treated plants grown in soil; (C) Untreated plants grown in hydroponics; (D) P33G-treated plants grown in hydroponics.

Plants that have been treated with P33G start producing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that repel pests such as aphids and the destructive Diamond Back Moth. “The leaves produce volatile compounds that ‘repel’ the insects, and they start avoiding these microbially-induced plants,” explained Prof. Swarup.

In contrast to traditional pest control products, this microbial solution doesn’t eliminate pests but instead outwits them. It transforms the plant into something that insects are no longer inclined to consume. At the same time, the plant grows faster, becomes sturdier, and captures more carbon through enhanced photosynthesis.

This innovative dual-action approach is the first of its kind. According to Prof. Swarup, “There are three novelties: first, it’s the only microbial solution using the principle of multitrophic interactions in pest management; second, it provides protection against a broad range of pests; and third, it combines insect tolerance with growth promotion.”

Field trials carried out at a commercial farm in Lim Chu Kang, Singapore, validated the laboratory findings: P33G-treated crops exhibited more robust growth and experienced fewer pest attacks. Concurrent trials in India are being conducted to evaluate the performance on a larger scale in expansive open-field farms.

The technology is currently applied to leafy greens such as choy sum but has potential for other vegetable crops. It is particularly well-suited for urban farms and controlled-environment agriculture, both of which are increasingly popular across Southeast Asia.

The approach also shows potential for lessening the environmental footprint of agriculture. In fact, annually, tens of thousands of tonnes of synthetic pesticides contaminate groundwater and harm ecosystems. “Transitioning to ecologically-based pest management strategies such as this can mitigate these negative impacts while maintaining food production,” Prof. Sanjay emphasized.

Improved root and shoot growth may also contribute to carbon sequestration, making this a rare agricultural technology that actively helps in mitigating climate change.

The initiative started with seed funding from NERI and evolved through collaboration with DBS, where entomology expertise and analytical equipment such as GC-MS facilitated the discovery of the plant-insect-microbe dynamics. The team has since filed a provisional patent and is currently exploring commercial partnerships with urban farms and agri-tech firms in Southeast Asia.

Although regulatory approval for consumer safety remains necessary prior to commercial rollout, interest from the industry is already strong.

As the world searches for sustainable ways to grow more food with fewer inputs, this multitrophic microbial advancement could be revolutionary. “We are open to collaborations in Singapore and beyond,” says the team. “This is just the beginning.”

For more updates on this and other research innovations, follow NERI’s channels and the team to stay tuned for developments as this powerful microbe takes root—literally—in farms of the future.

For more information regarding this research, please contact Assoc. Prof. Sanjay Swarup at dbsss@nus.edu.sg.